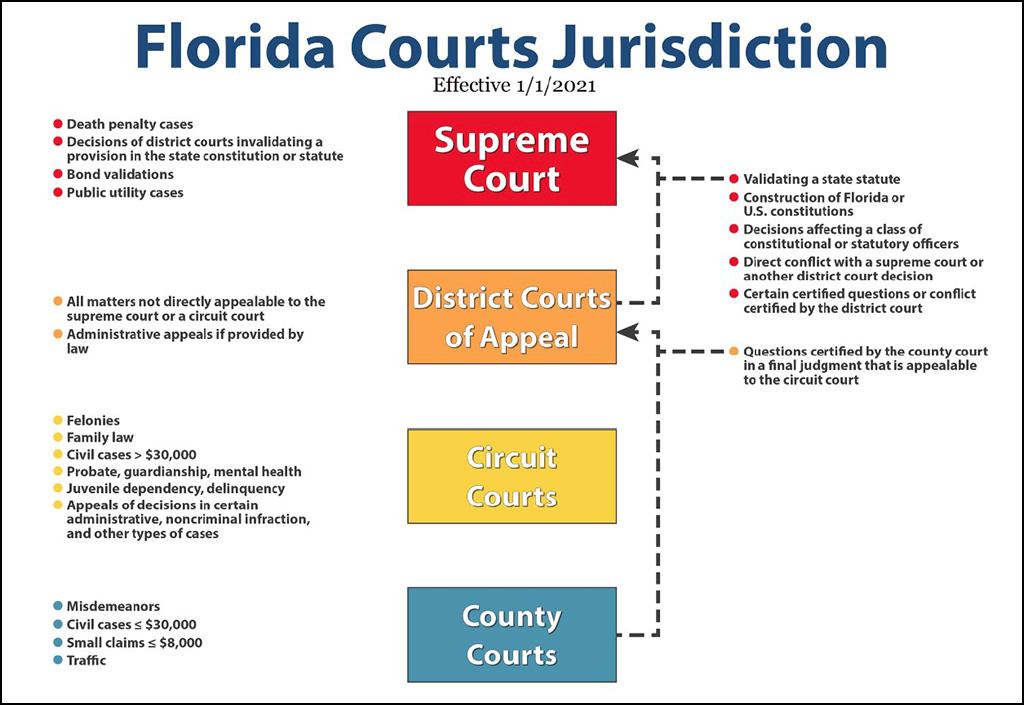

This chart is a general guide to the jurisdiction of courts in Florida. The bullets on the left side of the chart specify matters within the primary jurisdiction of the court and the bullets on the right side specify appeals for which the Florida Supreme Court and Florida District Courts of Appeal have discretionary jurisdiction. This chart is not intended to be comprehensive; many exceptions and distinctions exist.

This chart is a general guide to the jurisdiction of courts in Florida. The bullets on the left side of the chart specify matters within the primary jurisdiction of the court and the bullets on the right side specify appeals for which the Florida Supreme Court and Florida District Courts of Appeal have discretionary jurisdiction. This chart is not intended to be comprehensive; many exceptions and distinctions exist.

Florida Civil Appeals

Florida Appellate Courts

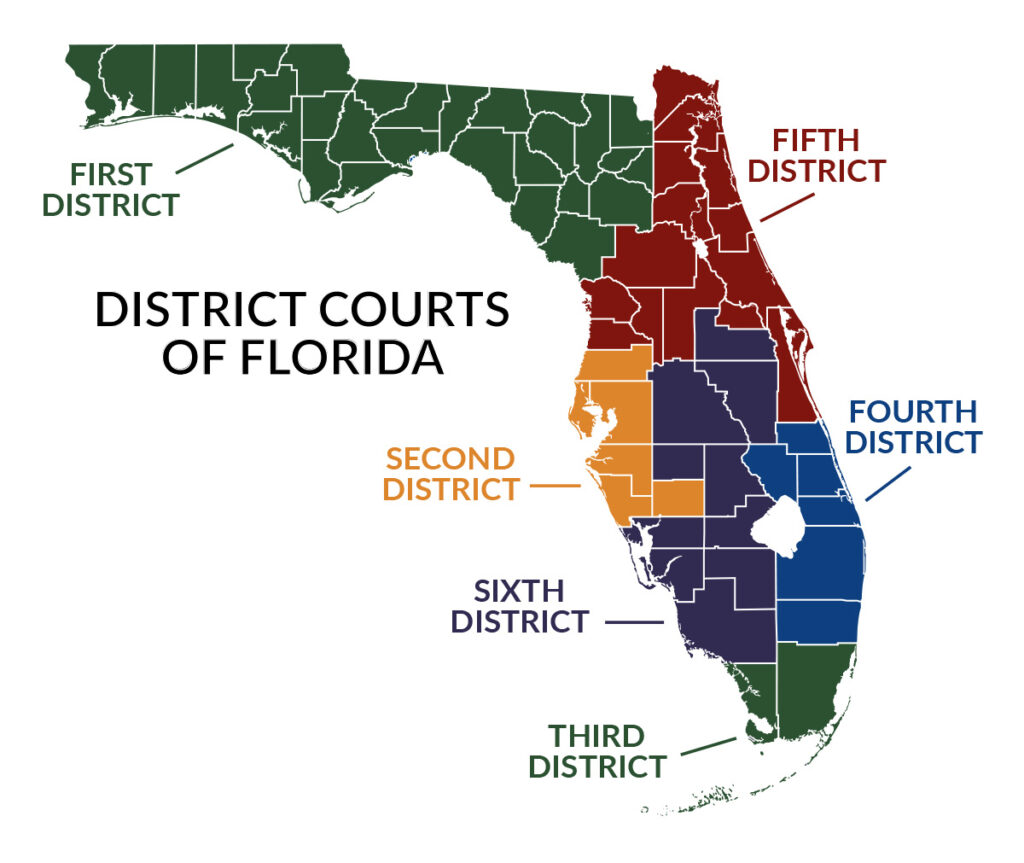

There are six district courts of appeal in Florida:

First District Court of Appeal – Tallahassee

Second District Court of Appeal – Tampa

Third District Court of Appeal – Miami

Fourth District Court of Appeal – West Palm Beach

Fifth District Court of Appeal – Daytona Beach

Sixth District Court of Appeal – Lakeland

Decisions from the circuit civil courts go directly to one of these district courts of appeal.

Some decisions from these six district courts of appeal can be appealed to the Florida Supreme Court in Tallahassee but Florida Supreme Court jurisdiction is very limited!

So as a general rule, for all practical purposes, Florida’s six district courts of appeal are courts of last resort.

Florida Federal Appeals

The House Judiciary Committee establishes the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure, which we often must use in conjunction with the local rules of the federal circuit courts of appeal. We have extensive experience before the federal district courts and circuit courts of appeal, including the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals, the governing federal circuit for Florida.

Appeal versus Trial

At trial, an attorney’s major objective is to persuade the fact-finder—typically a panel of lay jurors—that credibility lies on the side of his or her client’s witnesses, and the evidence, although controverted, favors his or her client. Trial lawyers ascertain the factual strengths and weaknesses of both sides of their cases, and then sift, select, and evaluate the evidence to be presented. To be successful, the trial lawyer must build a convincing argument from an amorphous mass of testimony and create an aura of righteousness around client and cause.

FLORIDA APPEALS FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

STANDARDS OF REVIEW IN APPELLATE COURTS

The appellate lawyer, by contrast, deals primarily with the law, not the facts; he or she argues to judges, not to lay juries. The focus of the appellate specialist is on legal argument, through written and oral advocacy. Broadly stated, appellate practice involves the practice of law before appellate courts. The function of appellate courts is, of course, to review the decisions of lower courts to determine if reversible error has been committed. Such review involves the interpretation and application of the law to a given set of facts.

Appellate judges are different from trial judges. Judges on appeal don’t reweigh facts, or judge credibility of witnesses. The job of the appellate court is to determine if legal errors were made in the trial court that were harmful and affected the outcome of the case. If the appellate court is convinced harmful error occurred, the judgment can get reversed.

At the appellate level, therefore, the aim of the appellate lawyer is to be persuasive and to effectively assist the appellate courts in accomplishing their review and decision-making objectives. In accomplishing this goal, the appellate practitioner must be proficient in several key areas, including, but not limited to: brief writing; oral argument; and rules of appellate procedure. Knowledge and experience in the appellate process are central to attaining such proficiency, as they would be with respect to any other field of law.

Navigating the Florida Rules of Appellate Procedure

In the appellate arena, there exist several procedural “landmines” which, as a general rule, are more easily navigated by the experienced appellate practitioner. The answers to many procedural dilemmas that arise cannot always be found in the Florida Rules of Appellate Procedure; often, such answers may be derived only through experience in the workings of the state appellate process, as well as an understanding of the case law and the local rules of each court. Potential “landmine” issues that can cause serious problems for the average practitioner include the following:

1) What constitutes “rendition” of an order for purposes of taking an appeal?

2) What post-trial motions toll the time for taking an appeal?

3) Which interlocutory orders are appealable as “appealable nonfinal orders”?

4) Which interlocutory orders are proper subjects of petitions for writ of certiorari, petitions for prohibition, or other extraordinary writs?

5) Which “partial final judgments” can be appealed, and which must be appealed, within 30 days?

6) What is a final order subject to appellate review?

7) Does a motion for rehearing (or motion for reconsideration) ever toll the time for taking an appeal from an interlocutory order?

Post Judgment Proceedings

“It’s never over until it’s over.” At least until you’ve exhausted the appellate process and your post-trial remedies.

You receive a “final” judgment or order in the trial court. Is it really final? If you believe that mistakes were made in the trial court, you can appeal that judgment or order to a higher court.

And if something happens after a final judgment, like mistakes; inadvertence; excusable neglect; newly discovered evidence; or fraud, you may be able to file a motion for post-judgment relief and vacate that final judgment.

Before the Judgment

Appeals can also be very helpful before a judgment is entered. There are many orders that can be challenged before the case has concluded without a judgment – such as those orders that

(A) concern venue;

(B) grant, continue, modify, deny, or dissolve injunctions, or refuse to modify or dissolve injunctions;

(C) determine

(i) the jurisdiction of the person;

(ii) the right to immediate possession of property, including but not limited to orders that grant, modify, dissolve or refuse to grant, modify, or dissolve writs of replevin, garnishment, or attachment;

(iii) in family law matters:

- the right to immediate monetary relief;

- the rights or obligations of a party regarding child custody or time-sharing under a parenting plan; or

- that a marital agreement is invalid in its entirety;

(iv) the entitlement of a party to arbitration, or to an appraisal under an insurance policy;

(v) that, as a matter of law, a party is not entitled to workers’ compensation immunity;

(vi) whether to certify a class;

(vii) that, as a matter of law, a party is not entitled to absolute or qualified immunity in a civil rights claim arising under federal law;

(viii) that a governmental entity has taken action that has inordinately burdened real property within the meaning of section 70.001(6)(a), Florida Statutes;

(ix) the issue of forum non conveniens;

(x) that, as a matter of law, a party is not entitled to immunity under section 768.28(9), Florida Statutes; or

(xi) that, as a matter of law, a party is not entitled to sovereign immunity.

(D) grant or deny the appointment of a receiver, and terminate or refuse to terminate a receivership.

Extraordinary Writs

And then there are extraordinary writs. These are possible when you want to challenge certain pre-trial rulings. For example, you can use a petition for certiorari to protect you from having to disclose confidential, privileged, or trade secret information in the discovery process.